By Nicola Bryan, BBC News

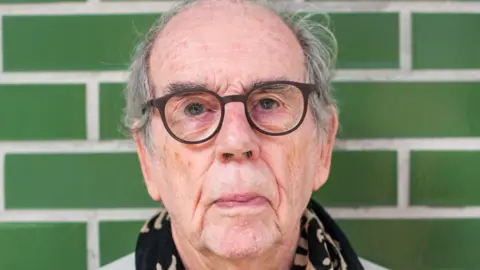

Pete Boyd

Pete BoydIn the picturesque village of Tintern, in south Wales, an elderly gentleman can often be found taking pictures at community events and family celebrations.

But David Hurn, 89, is far from your average photographer.

Over the past seven decades he has documented everything from the Aberfan disaster to the Beatles at the height of Beatlemania.

In the ’70s he set up Newport’s prestigious School of Documentary Photography, producing scores of photographers.

And these days the man often described as Wales’ most important living photographer has streams of new admirers, after getting to grips with social media.

David Hurn / Magnum Photos

David Hurn / Magnum Photos“Twitter and God knows what… I don’t even know what they all mean, I just don’t understand it,” he said.

“But I suddenly discovered that there was this thing called Instagram.”

In 2016, the self-taught photographer casually started an account on the social media platform, sharing his musings on photography and photos taken throughout his career.

Now these Instagram posts – which have helped him build up a following of more than 54,000 Instagram followers – have been brought together in a photo book titled David Hurn: On Instagram.

David, who was raised in Cardiff, never intended to become a photographer.

In fact he had his heart set on becoming a vet, but his dyslexia meant he left school with no qualifications.

David Hurn / Magnum Photos

David Hurn / Magnum PhotosNational Service and a transfer to The Royal Military Academy Sandhurst followed.

One day he was in the officers’ mess – the social space and accommodation for personnel – when he picked up a copy of the magazine Picture Post and became overwhelmed by an image on one of its pages.

“Suddenly I started to cry really quite violently. It was not just little tears, it was big sobbing,” he said.

The image was of a Russian army officer buying his wife a hat in a department store in Moscow.

It triggered a memory of his own father returning from World War Two and taking him and his mother to Howells department store in Cardiff and buying her a hat.

“It was the first memory I had of the love between my mother and my father,” said Hurn.

“I instantly realised that all Russians don’t eat their children.

“This one simple picture I believed more than the propaganda.”

On leaving Sandhurst he headed for London.

“I kind of learnt photography by sitting in the coffee bars and shooting a bit,” he said.

It was in a coffee bar that he met the politician Michael Foot, who at that time was working as a journalist.

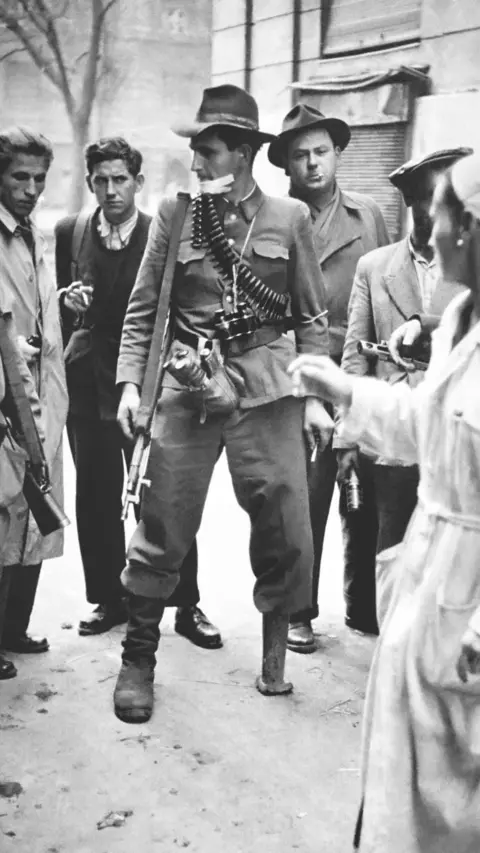

Foot told him about the unfolding uprising in Hungary and suggested he go there and take pictures – and that is exactly what he did.

He got into Budapest in an ambulance after contacting the Red Cross.

He met journalists from Life magazine whose photographer had been unable to get into the city so he was asked to work for them.

“Little did they know that I was up in my room reading my book on how to put film in my camera,” laughed David.

“I learned very quickly that it’s better to start at the top than the bottom.

“If you start at the top you just cling on and learn very quickly.”

His first pictures appeared in Life Magazine and then the Observer.

He said: “Suddenly, sort of, at the age of 22 I had a name.”

David Hurn / Magnum Photos

David Hurn / Magnum PhotosHurn quickly built a career covering current affairs, but it was not long before his career took a more glamorous turn.

One of the first big stars he photographed was Sophia Loren while she was making the film El Cid in 1960.

“Sophia was wonderful. We became very good friends and so we would eat every night together,” said Hurn.

When the fashion magazine Harper’s Bazaar wanted Loren to do a fashion shoot, she agreed to do it on the condition that Hurn took the pictures – which led to more fashion work.

David Hurn / Magnum Photos

David Hurn / Magnum Photos David Hurn / Magnum Photos

David Hurn / Magnum PhotosIn 1963, Hurn was asked to take publicity shots of Sean Connery for the Bond film From Russia with Love.

“Now that’s a very funny story,” he laughed.

They were in Hurn’s west London studio to shoot the poster when the publicist realised they had forgotten to bring the gun for Connery to pose with.

“I said ‘don’t panic, one of my hobbies is target shooting with a pistol,” said Hurn.

He produced his Walther air pistol which can be seen in the finished poster.

David Hurn / Magnum Photos

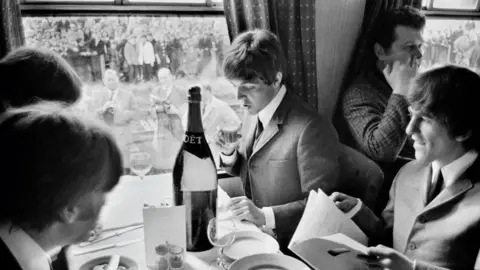

David Hurn / Magnum PhotosThe following year, at the height of Beatlemania, he spent about seven weeks photographing John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison and Ringo Starr at Abbey Road Studios during the filming of A Hard Day’s Night.

“I got on with them very well,” he said.

“I must be one of the few people that’s played Monopoly with The Beatles.”

And he said he spotted some tension between the band.

David Hurn/ Magnum Photos

David Hurn/ Magnum Photos“I wasn’t totally convinced that they actually really liked each other all that much,” he said.

“It didn’t surprise me when they quickly broke up later.”

What were they like?

“I found John a little bit aloof to everybody… Paul had an attitude of being slightly pompous, absolutely understandable because it turns out that he was really the guy writing the thing, George was off on a world of his own… and Ringo was just a nice guy. I found him lovely.”

He went on to spend that Christmas with Ringo.

David Hurn / Magnum Photos

David Hurn / Magnum PhotosOver the years he photographed an array of film stars, including “extraordinary looking little elf” Audrey Hepburn, Jane Fonda, who remains a friend, Michael Caine, Vanessa Redgrave, Peter O’Toole and Al Pacino.

Hurn has also become celebrated for his photos of everyday people living their everyday lives, what he likes to call “the exotic of the mundane”.

His long and varied career has also taken in some key moments in history.

On 21 October 1966, a colliery spoil tip in the south Wales village of Aberfan collapsed, killing 116 children and 28 adults.

David Hurn / Magnum Photos

David Hurn / Magnum PhotosAt the time Hurn was in Bristol with fellow Magnum photographer Ian Berry when news came through on his car radio and they headed straight to the village.

Speaking on the 50 year anniversary on the disaster in 2016, he told the BBC: “One of the main recollections I have is the strong feeling that they didn’t want us there.

“I didn’t talk to anybody, I don’t think, at all the entire time. But I very consciously made the decision that I needed to be there.”

In 1973, Hurn set up Newport’s School of Documentary Photography.

“There’s a part of me that says it was 15 years I wasted when I could have been shooting pictures,” said Hurn.

“But I have to admit this to myself, there’s a really large group of young people who spent their lives having a very pleasant life being photographers who almost certainly wouldn’t have if it hadn’t been for me… it is actually probably more important than my pictures.”

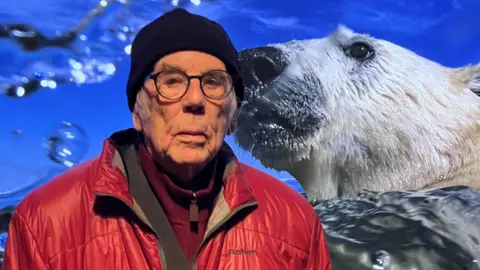

Hurn, who will turn 90 in July, is still busy working, with two more books in the pipeline.

He has also begun inviting students into his home in Tintern, Monmouthshire, offering them coffee and a chat about photography in exchange for them working on his overgrown garden.

“So I’m setting up a slave labour department,” he joked.

David Hurn

David Hurn What work he is proudest of? A very difficult question to answer, he said.

“I’ve become the village photographer, so I cover little Johnny’s birthday party and this and that and I do it very seriously, as though I was working for Life magazine, and I love doing that.”

It turns out his emotional reaction to a photograph almost seven decades ago would be the catalyst for a full and much celebrated career.

“I’ve had a blissful, blissful, blissful life,” he said.

“I’m having fun.”